In 2009, Maltese author Antoine Cassar won the United Planet Writing Prize for his multilingual composition Merħba, a poem of hospitality. The prize was a two week Quest to Sungal, a small village in the far north of India. What a beautiful and inspirational experience he had…

Many thanks to Antoine for his beautiful story, and wonderful photos.

I awake to the sound of torrential rain, and to the constant pouring of water from the roof of the camp onto the inundated lawn outside my window.

The tiny town of Sungal, deep inside the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh

Here in tiny Sungal, a snaking seven-kilometre mountain road away from the town of Palampur, deep inside the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh, the humidity would be stifling were it not for the lush swathe of green that straddles the foothills of the Himalayas.

It is coming to the end of the monsoon season, and although the sun is not shy to peep out at least once a day to mark its imprint on the balding crown of my head, the bone-cooling dampness is constant, and clothes take almost a week to dry.

In fact, it wasn’t until the day before leaving that the thick cloud would retreat completely, to welcomingly reveal the breathtaking peaks at the end of the valley, and how close they actually were.

The seven children Antoine had the pleasure of teaching

After the early-morning dose of spirituality and sweetness (a yoga session led by Sanji, followed by Auntie Ji’s cinnamon tea and scrumptiously simple banana chapathi), it’s time to prepare the day’s lessons.

I spend the mornings with a group of seven boisterous, sprightly and extraordinarily respectful mentally-challenged kids, teaching them simple English and maths, singing songs and, weather permitting, playing sports and going for walks in the nearby forest.

If I were to say that I have never before seen children so jubilant to attend school, I would not be exaggerating in the least. Highly affectionate from the second I met them, the energy that their hyperactivity drained out of me each morning would quickly be replenished with their smiles and laughter.

No material comforts are needed: there are no tables and chairs, for example, only a mat rolled out on the hard floor, which you quickly become accustomed to, and which, I eventually discovered, has a double advantage: not only are teachers and pupils on the same level, but it is easier to sit in a circle, so that no child feels distant from the centre of the action.

We are playing a card game I invented on the spot, to practice the order of numbers in English and in Hindi, counting backwards and revising simple addition and subtraction. Raja, a usually quiet 7-year-old boy with Downs’ Syndrome, is thoroughly enjoying himself, throwing his cards down with joyful force, bringing out all the contagious charisma he appeared so much to like to hide. ‘

Raja’ is the Sanskrit word for monarch, and his tough, lively character quickly earns him the nickname of ‘Raja the King’. On a couple of occasions, his over-enthusiasm leads him to pick a fight with his two older companions Lekhraj and Anish; I swiftly carry him outside to sit in the garden and calm him down.

Outside the school in Sungal

After a couple of minutes we become friends again, as he turns to look at me with the face of a bashful angel. At that very moment, I realize how excruciatingly difficult it will be to leave him only days later.

After Aunty Ji’s nourishing lunch and an enchanting Hindi lesson with Rushika, I am taken to Padhiarkhar, a tiny collection of houses down the road, almost floating within a sea of rice paddies.

Out on the patio of one of the homes, with a backdrop of fields leading to the mountains, I teach a group of bright teenage girls who apparently, until only months before, had never had the opportunity to go to school. Yet they are far from illiterate, and their level of English is astounding. Together with Ditte, a volunteer from Denmark, we introduce each lesson with a geographical memory game.

With the help of a transparent, inflatable globe, each girl ‘adopts’ a country beginning with the same letter as their name: Anjeli chooses Argentina, for example, and Jamuna sets her eyes on Jordan. (Regrettably, none of the girls’ names begin with M, so there is nobody to adopt tiny Malta…)

They note the particular shape of their adopted countries, as well as the typical animals and fruits of each place; on the final day, after two weeks throwing the globe to one another and testing each other’s memory, completing the world map jigsaw I very luckily came across at the camp is as easy as daal.

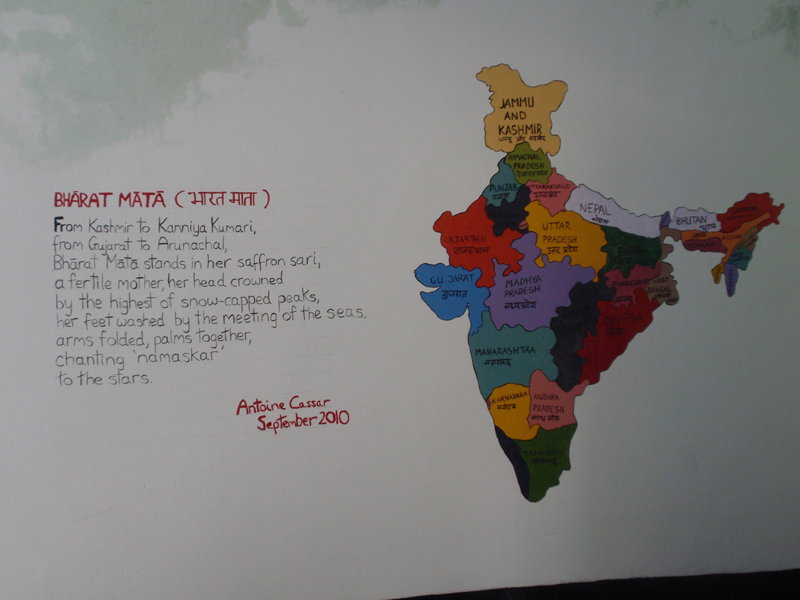

A painting of India as well as a poem written by Antoine on the back wall of one classroom

Before leaving Sungal for a series of poetry readings down south, I join a group of fellow volunteers who have been given the task of painting classrooms in another village.

On the back wall of one classroom, two volunteers had just painted a colourful, accurate map of India. Encouraged by the headmaster, and with the help of the expert hands of Ana and Sanji, we paint the final lines of a new poem I had written the day before describing the shape of the subcontinent: perhaps a shark fin, perhaps a broken heart, or the udder of a sacred cow…

The ending of the poem is inspired by the image of Bhārat Mātā (Mother India) I had seen in a school text book, clad in a saffron sari, her head crowned by the snow-capped peaks, her feet washed by the meeting of the seas.

One week later, during a seminar at a university in Kolkata, I was to discover that the saffron sari –the detail of my poem that the village headmaster told me he liked the most– was a representation intensely abused over the years by the ultra-right-wing BJP party… I immediately modified the poem to include a rainbow sari. If only I had known that before the lines were painted on the wall of the Himachal school!

Students and teachers in Padhiarkhar

Averse as I am to dressing up beyond what is truly necessary, one of the simplest, most meaningful everyday aspects of my stay in India was the fact that all buildings –including the classrooms and the outdoor patio in Padhiarkhar– were to be entered barefoot. I found this custom to be of special significance when later visiting families in Shantiniketan and Bangalore.

There is something very mystical in the act of removing your sandals to enter a family home, feeling the cool floor against the soles of your feet, the same floor that the hosts walk on, work on, sleep on, live on.

The true poem of hospitality, I was to discover, was not the one I had written a year before; it does not need to be composed in several languages, nor even in a single tongue.

The earthy coolness of those floors, the warm and convivial gestures exchanged with the members of the family, the generous aromas of chai and spices slowly filling the room, prove more than enough to bridge the differences between the two meeting cultures. Such is, I slowly learnt, the profound charm of hospitality: the beauty of humanity welcoming itself.”

ABOUT UNITED PLANET

United Planet is a non-profit organization with a mission to create a global community, one relationship at a time. Established in 2001, United Planet offers volunteer abroad, virtual internships, internships abroad, gap year volunteering, and global virtual exchange in more than 40 countries.